Summertime is when I can catch up some in reading the philosophy journals. This can be tedious work since much philosophy, to be frank, is overly technical and picky. The payoff is when an article one hardly expects anything from yields riches. This was the case for me today reading Andy Hamilton's "Scruton's Philosophy of Culture: Elitism, Populism, and Classic Art." British Journal of Aesthetics 49:4 (2009) 389-404. Roger Scruton (perhaps the leading living English-speaking aesthetician/philosopher of art today) prides himself in being an elitist, although he also thinks that the elite product has meaning insofar as it relates to the emotions and aspirations of all. It may be easy for some to simply dismiss Scruton as an arch conservative, and he certainly does often seem to identify with upper-class values as such. Yet, although politically a left-liberal, I have long felt a strong affinity for Scruton's work in aesthetics and his critique of kitsch. Hamilton does a nice job of showing why Scruton has something to offer us on the concept of "elitism" and in his defense of what he calls "high culture." Hamilton rejects these two terms, but mainly because of associations he does not want to advocate. One has to be careful with the definition of elitism, and if you use it in a theory you have to be very clear about the sense in which it is used. Hamilton defines elitism as "denial of populism...[in] the sense which rejects the possibility of better judgment in moral, aesthetic, and cultural matters." His view is not to be confused, then, with elitism as defined by anti-egalitarianism. In short, the elitism Hamilton defends (actually, in the end he just dumps the term "elitism" in favor of "meritocracy") is not the idea that there is a class of people, commonly an aristocracy, which counts as "the elite" and whose taste is to be regarded as superior. He would not support elitism in that sense. His defense of elitism is more in line with David Hume's idea (in "Of the Standard of Taste") that there are certain works of art that are of great value, a value which can be perceived by those who have taste in that domain, those people being the "good judges" which, Hamilton would say, is another way of referring to the cultural elite in a cultural meritocracy.

Hamilton calls these works "classics." I find this problematic since some of the most valuable works, especially important works of our own time, are not classics. For one thing, they have not had the time to stand what Hume famously calls "the test of time." Hamilton would reply to this objection that "The concept of the classic is backward-looking in making essential reference to the test of time, but clearly one must allow that new works can belong to high culture: contemporary high culture is that which critical opinion predicts will become classic." (401) However I think that even works that may never stand the test of time can still be of immense value, value that is recognized by people with the appropriate taste. And yet that value is perhaps more in the innovative nature of the work than in refinement and thus does not meet the standard of what we ordinarily consider to be taste when that is associated with things called classics. Think of really crude but wonderful examples of early blues music. Such works only get to be called "classic" honorifically since they are at the beginnings of the great blues tradition. Does Hamilton's notion of "classic" allow in the possibility of a greatly innovative, but raw at the edges, garage band? Think of the Beatles. Their earliest music was by no means classic. If we think of classic Beatles we think of Abbey Road or The White Album. However, the greatness of the Beatles also includes the raw energy of their early underground club work. My only problem with Hamilton then is that he (and perhaps also Hume) do not allow for that which is aesthetically great or valuable but also not really even connected to the test of time: both of their views are a bit too backwards-looking. OK one could argue that the early music of the Beatles can be brought into the domain of the classic retroactively because it leads too their truly classic rock productions. But that somehow misses the point. Hamilton fails to recognize that "classic" is invariably connected with a classical style, which, in Nietzschean terms, is fundamentally Apollonian, not Dionysian. And to say that the good new stuff is predicted or predictable by the person of taste to pass the test of time in the future misses one very important historical fact: widely recognized "persons of taste," for example very good art critics, have typically failed to properly appreciate great innovative works when they first came out and in their cruder more formative stages. A sign of the limitation of the concept of "the classic" is when Hamilton writes "Classics are timeless and transcendental, appealing to all historical eras, because they capture what is essential about humanity." (403) That is OK as a definition of "the classic" but I wouldn't want to hang a theory of taste or aesthetics or value on art on it since I think we can have taste in all sorts of matters that do not fit this definition at all.

As mentioned above, Hamilton prefers the term "meritocracy" to "elitism" in being concerned with the "classic" rather than with "high culture." ("High culture" like "elitism" has, as he adequately shows, too many awkward and anti-democratic associations.) He also believes it is a more positive response to populism. One of the main ideas of meritocracy is that those who have good taste can come from any part of society. Meritocracy, on Hamilton's view, is not even inconsistent with a democratic approach since "even the novice's response has a status in critical discourse." (397) (Let me interject here the same problem: Hamilton only gives the novice a role insofar as the novice debates with the good judge and comes to see in the process of debate that he or she was wrong. Again, this does not give enough credit to the revolutionary nature of the thinking of some novices who, in debate with the good judge, overthrow the applecart, and in a good way.) Hamilton correctly sees that Hume is not elitist in the sense of limiting taste to a certain class. As I have argued elsewhere, for Hume, critical authority comes from practice and comparison that gives rise to delicacy of sentiment within the very area in which practice and comparison has occurred (this also requires good sense and lack of prejudice, as Hume observed). What the area is is neutral: it could be opera or hip-hop. No social hierarchy of art forms is required by Hume's conception of taste. For Hamilton, "Meritocracy denotes a system of social organization where appointments are made on the basis of ability rather than wealth, family connections, or class" (398) and he extends this to artistic appreciation. So, for Hamilton, "meritocracy requires an open, non-exclusive body of authorities, and a nuanced notion of authority,., It agrees with elitism that some individuals are more penetrating judges of moral, cultural, and spiritual questions, and should have social influence; it denies that the resulting body of authorities is exclusive." (398) To elaborate the last point, "even if, as elitism asserts, some people are more penetrating judges of cultural and moral questions than others, each individual must ultimately decide these questions for themselves." (398) (Again, this "decide for yourself" element does not really take into account valuable revolutionary work) He also rightly sees that, for Hume, the less experienced art viewers do not simply defer to the man of taste but debate with him, and by doing that, can eventually become good critics themselves. Here, then, is my favorite quote from the article (the one that made me decide to write this post):

"It would be perverse for someone to say 'I just defer to critical opinion. If I want to buy a painting by a contemporary artist, or recordings of Jamaican dub music, I'll ask an expert's opinion on which to go for. I'm not interested in developing my own autonomous judgment. This aesthetically heteronomous individual mistakes the beginning of the process of appreciation for its end. But the opposed extreme is also misguided. 'I never read the critics. I just form my own judgment' - the claim of the aesthetic solipsist - and 'I never form my own judgment, I just read the critics' are equally perverse." (399)

Hamilton wishes to replace Scruton's concept of "high culture" with that of "the classic," which would include not only that which has stood the test of time and "which demands, and best awards, seriousness and intensity of intention" (400). "Classic," unlike "high culture" includes all popular and functional genres as well as traditional high culture items, and it is not limited to any ethnic group either. Classic, for Hamilton, means "excellent of its kind." This allows it also to include design classics such as the Braun alarm clock. (I also have a problem with associating aesthetics exclusively with classics in this sense: it excludes those aspects of the aesthetics of everyday life which are not tied to works of classic design, for example the pleasure one gets in owning a watch that one recognizes is far from being a design classic, but rather has other redeeming qualities.)

Hamilton concludes his essay rather nicely: "'Meritocracy' and 'classic' are far from ideal terms, but I believe that they are an improvement on 'elitism' and 'high culture'. It is regrettable, therefore, that only an exclusive, self-perpetuating group of intellectuals will ever really understand the analysis of culture I have offered." (404) It is!

Showing posts with label Scruton. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Scruton. Show all posts

Thursday, July 28, 2016

Thursday, June 2, 2016

Scruton on poetry, truth, Heidegger and everyday aesthetics

Roger Scruton's "Poetry and Truth," in The Philosophy of Poetry (Oxford, 2015) ed. John Gibson (149-161) is one of the more interesting discussions of the topic, especially given that Scruton begins with a discussion of Heidegger's concept of poetry as "the founding of truth" which Scruton takes to be true! Scruton rightly takes "truth" to refer here not to evaluation of sentences in terms of truth value, so loved by Frege and friends, but in the sense of revelation, or as Heidegger would put it, unconcealment. Poetry, according to Heidegger, is a bringing forth which is also a bestowing. Scruton says that Heidegger is "attempting to gives a secular version of [a religious idea of revelation]. And by attributing the process of revelation to poetry - in other words, to a human product, in which meaning is both created by human beings and also 'bestowed' by them he can be understood as advocating revelation without God." (150) In relation to my posts on aesthetic atheism, I like Scruton's idea, taken from Wagner's essay "Religion and Art," that "religions have all misunderstood their mission, wishing to propose as true stories what are in fact myths...that cannot be spelled out in literal language." (150) and that "the meanings of the myths must be grasped through art, which shows us the concealed deep truth of our conditions, in dramatized and symbolic form." He also mentions (as a more bleak view) Nietzsche's similar idea that we need art "so that we will not perish of the truth" i.e. that God is dead.

For Scruton, "the heart of poetry is the poetic use of language" i.e. as distinct from everyday and scientific uses, a use that involves figures of speech that do not describe connections but make them in the mind of the reader. He makes a strong distinction between the poetic and the prosaic use of language, the later being instrumental, having the property of aboutness, having an interest in truth as correspondence, and having substitutivity of equivalent terms.

Scruton says that Keats in his "Ode to the Nightingale" "does not describe the bird and its song only: he endows it with value. The nightingale shares in the beauty of its description, and is lifted out of the ordinary run of events, to appear as a small part of the meaning of the world." I have argued elsewhere that Scruton originated the idea of the aesthetics of everyday life back in the 1970s, although, of course, the true grandfather of the movement was John Dewey. Scruton has continued to make major contributions to the field, most notably in his book Beauty. I have also argued that everyday aesthetics happens when the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and that that often happens when everyday phenomena are seen with the eyes of the artist. Scruton shows, through the Keats example, how poetry can make this happen. As he puts it "poetry transfigures what it touches, so that it is revealed in another way" and the test is "truth" in something like Heidegger's sense. Scruton understands the idea of poetry bestowing truth partly in this way: Eliot in Four Quartets "is looking for the sincere expression of a new experience, one that will remain true to its inner dynamic, and how what it is to live that experience in the self-awareness of a modern person. He is looking for words that both capture the experience and lend themselves to sincere and committed use." (159) Yet Eliot's idea may seem overly subjective. By contrast, Heidegger insists on an objective dimension in the grounding that poetry bestows.

Scruton finds in Rilke's "Ninth Elegy" the source of Heidegger's thought, where the truth of the thing, e.g. the house, "is a truth bestowed in the experience." Further "Its measure is the depth with which these things can be taken into consciousness and made part of a life fully lived." (160) So Scruton concludes that there is an inner truth to things, one bestowed by poetry, and that this inwardness is of our experience: "the fusing of a thing with its associations and life-significances in the poetic moment" (161) i.e. achievements that are "fruit of a life lived in full awareness."

Over time, I have become a bigger and bigger fan of Scruton (don't like his politics): he has the broad vision one might call wisdom and stands far above the usual in the realm of analytic aesthetics. Here is one final quote: we question what is the meaning of a world that has come to this: "The right answer is that answer that enables us to incorporate the things of this world into a fulfilled life. For each individual object, each house, bridge, fountain, gate, or jug, there is such an answer. And the poet is the one who provides it....His answer is true when it shows how just such a thing might be part of a fulfilled human life..."

For Scruton, "the heart of poetry is the poetic use of language" i.e. as distinct from everyday and scientific uses, a use that involves figures of speech that do not describe connections but make them in the mind of the reader. He makes a strong distinction between the poetic and the prosaic use of language, the later being instrumental, having the property of aboutness, having an interest in truth as correspondence, and having substitutivity of equivalent terms.

Scruton says that Keats in his "Ode to the Nightingale" "does not describe the bird and its song only: he endows it with value. The nightingale shares in the beauty of its description, and is lifted out of the ordinary run of events, to appear as a small part of the meaning of the world." I have argued elsewhere that Scruton originated the idea of the aesthetics of everyday life back in the 1970s, although, of course, the true grandfather of the movement was John Dewey. Scruton has continued to make major contributions to the field, most notably in his book Beauty. I have also argued that everyday aesthetics happens when the ordinary becomes extraordinary, and that that often happens when everyday phenomena are seen with the eyes of the artist. Scruton shows, through the Keats example, how poetry can make this happen. As he puts it "poetry transfigures what it touches, so that it is revealed in another way" and the test is "truth" in something like Heidegger's sense. Scruton understands the idea of poetry bestowing truth partly in this way: Eliot in Four Quartets "is looking for the sincere expression of a new experience, one that will remain true to its inner dynamic, and how what it is to live that experience in the self-awareness of a modern person. He is looking for words that both capture the experience and lend themselves to sincere and committed use." (159) Yet Eliot's idea may seem overly subjective. By contrast, Heidegger insists on an objective dimension in the grounding that poetry bestows.

Scruton finds in Rilke's "Ninth Elegy" the source of Heidegger's thought, where the truth of the thing, e.g. the house, "is a truth bestowed in the experience." Further "Its measure is the depth with which these things can be taken into consciousness and made part of a life fully lived." (160) So Scruton concludes that there is an inner truth to things, one bestowed by poetry, and that this inwardness is of our experience: "the fusing of a thing with its associations and life-significances in the poetic moment" (161) i.e. achievements that are "fruit of a life lived in full awareness."

Over time, I have become a bigger and bigger fan of Scruton (don't like his politics): he has the broad vision one might call wisdom and stands far above the usual in the realm of analytic aesthetics. Here is one final quote: we question what is the meaning of a world that has come to this: "The right answer is that answer that enables us to incorporate the things of this world into a fulfilled life. For each individual object, each house, bridge, fountain, gate, or jug, there is such an answer. And the poet is the one who provides it....His answer is true when it shows how just such a thing might be part of a fulfilled human life..."

Labels:

aesthetic atheism,

everyday aesthetics,

Heidegger,

poetic truth,

poetry,

Scruton,

thingliness,

truth

Monday, September 30, 2013

Roger Scruton on Kitsch

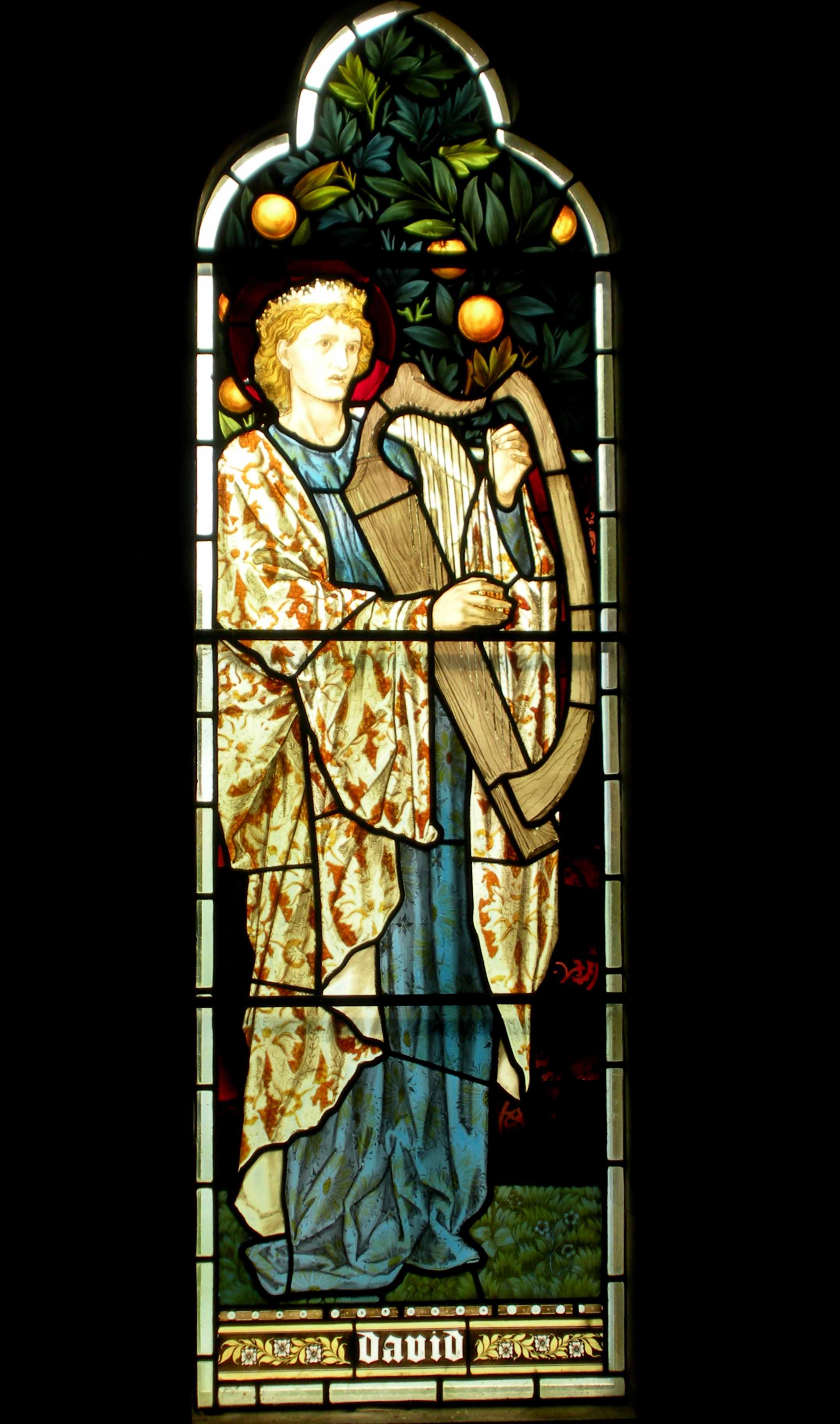

Burne-Jones angel, 1872 Waterford, Hertfordshire. Scruton thinks of this as kitsch. Source: Wikipedia.

Continuing my exploration of kitsch, consider the arguments against kitsch offered by Roger Scruton in his "Kitsch and the Modern Predicament," City Journal, 1999. Scruton begins with a discussion of Clement Greenberg's classical article on avant-garde and kitsch, except Scruton believes that even avant-garde art (including abstract art) can be kitsch. He gives Georgia O'Keefe as an example. I think that a lot of O'Keefe's work is great art, but some is at least borderline kitsch. What I am more interested in his Scruton's specific objections to kitsch. He believes that kitsch comes with modernity, i.e. that there was no kitsch prior to the 19th century. As with other critics of kitsch he sees it as cheap and sentimental art: "What makes for kitsch is not the attempt to compete with the photograph [as Greenberg believed was true of representational art] but the attempt to have your emotions on the cheap—the attempt to appear sublime without the effort of being so. And this cut-price version of the sublime artistic gesture is there for all to see in Barnett Newman or Frank Stella. When the avant-garde becomes a cliché, then it is impossible to defend yourself from kitsch by being avant-garde." Scruton is a notoriously conservative art critic and, as we can see here, he fails to see the sublime in Newman or Stella. Still, it is arguable that the avant-garde is as capable of cliché as representational art, that kitsch is a matter of getting emotions on the cheap, and that appearing to be sublime without any effort might be one example.

As I mentioned earlier, Scruton thinks that the art of earlier times was never kitsch: "The artless art of primitive people, the art of the medieval stonemasons and stained-glass makers—all these are naïve and devoid of high pretensions. Yet none is kitsch, nor could it be. This art never prompts that half-physical revulsion—the "yuk!" feeling—that is our spontaneous tribute to kitsch in all its forms." An interesting feature of this comment is that, unlike Robert Solomon, who famously focused on the "oh how cute" response to kitsch by kitsch-lovers, Scruton stresses the "yuk" response to kitsch by kitsch-haters. Both are equally important. Scruton gives us a clearer idea of kitsch when he says "Of course, stained-glass kitsch exists, but it is the work of Pre-Raphaelites and their progeny—the work of sophisticated people, conscious of their loss of innocence. We all admire the craftsmanship of Burne-Jones, but we are also conscious that his figures are not angels, but children dressing up." Yes, the work of the Pre-Raphaelites often does seem kitsch-like even though these pieces are much more likely to be found in museums than the work of Thomas Kincaid. Perhaps the kind of artificiality of angels that really look like children dressing up would itself be enough for something to be branded kitsch.

Scruton observes that the modernists were "keen anthropologists, looking for those "genuine" and unforced expressions of sentiment against which to weigh the empty clichés of the post-romantic art industry" [for example, the work of Bouguereau] but notes that cultures in previously pre-modern places like Africa quickly succumbed to kitsch in modern times: "today the mere contact of a traditional culture with Western civilization is sufficient to transmit the disease [of kitsch]" producing a plethora of tourist art which Scruton refers to as fakes.

One of my favorite Scruton quotes is: "In all spheres where human beings have attempted to ennoble themselves, to make examples and icons of the heroic and the sublime, we encounter the mass-produced caricature, the sugary pretense, the easy avenue to a dignity destroyed by the very ease of reaching it." He sees a prime example of kitsch to be the American cemetery Forest Lawn. Of course this is not art, but might be found under the definition of kitsch as an artifact that is overly sentimental: "In Forest Lawn Memorial Park, death becomes a rite of passage into Disneyland. The American funerary culture, so cruelly satirized by Evelyn Waugh in The Loved One, attempts to prove that this event, too—the end of man's life and his entry into judgment—is in the last analysis unreal. This thing that cannot be faked becomes a fake. The world of kitsch is a world of make-believe, of permanent childhood, in which every day is Christmas. In such a world, death does not really happen." The idea that kitsch promotes a "permanent childhood" and a fantasy where bad things never happen appears again and again in discussions of kitsch. Even death becomes something sweeter in works like Dickens' Old Curiosity Shop with the death of Little Nell is presented in a kitsch way, or in Disney's Bambi. (Is it kitsch when it is presented as children's entertainment, however?)

But when Scruton also says that "Kitsch is not just pretending; it is asking you to join in the game. In real kitsch, what is being faked cannot be faked. Hence the pretense must be mutual, complicitous, knowing. The opposite of kitsch is not sophistication but innocence. Kitsch art is pretending to express something, and you, in accepting it, are pretending to feel" one wonders whether he isn't making kitsch too complicated. Perhaps there is a kind of kitsch art where a knowing pretension is involved, but normally the enjoyment of kitsch just is lack of sophistication, which is, after all, another word for innocence. On the other hand, Scruton is right that kitsch involves the avoidance of anything that requires moral energy.

Scruton offers a fascinating theory of the nature of kitsch. He says

"We are moral beings, who judge one another and ourselves. We live under the burden of reproach and the hope of praise. All our higher feelings are informed by this—and especially by the desire to win favorable regard from those we admire. This ethical vision of human life is a work of criticism and emulation. It is a vision that all religions deliver and all societies need. Unless we judge and are judged, the higher emotions are impossible: pride, loyalty, self-sacrifice, tragic grief, and joyful surrender—all these are artificial things, which exist only so long as, and to the extent that, we fix one another with the eye of judgment. As soon as we let go, as soon as we see one another as animals, parts of the machinery of nature, released from moral imperatives and bound only by natural laws, then the higher emotions desert us. At the same time, these emotions are necessary: they endow life with meaning and form the bond of society. Hence we find ourselves in a dangerous predicament. The emotions that we need cannot be faked; but the vision on which they depend—the vision of human freedom and of mankind as the subject and object of judgment—is constantly fading. And in these circumstances, there arises the temptation to replace the higher life with a charade, a moral conspiracy that obscures the higher life with the steam of the herd."

So kitsch on his view arises from the need to replace a needed vision that is constantly fading and the temptation to satisfy that need with something that "obscures the higher life" and "higher feelings. After the decline of religion, Scruton argues, the Enlightenment attempted to solve this problem by seeing human judgment (as found in the great masterpieces of humanity) as giving us this higher value. But since this vision is not supported by faith, it loses power, and is replaced by the romantics who try to give give human products a religious aura. Perhaps humans can have the significance of angels. But then arose kitsch.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)